“Which one are you?” This is the question every woman and girl is asked at some point in her life. We all know who and what this question refers to without needing the context. Your answer to this question reveals your female archetype. Are you Miranda, Charlotte, Samantha, or…Carrie?

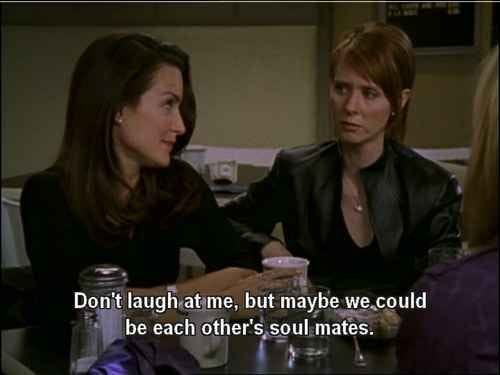

The cultural impact of Sex and the City has shaped our idea of American womanhood for nearly thirty years now. Each leading woman represents an archetype. Miranda is the shrewd and highly intelligent woman who is afraid to let her guard down in love but ultimately finds a patient mate who isn’t afraid of her intimidating exterior. Charlotte is the snobby, prudish wannabe tradwife with a heart of gold and a clear vision of what she wants. It’s only when she gets her prince charming that she realizes he doesn’t quite live up to the fantasy she had in her head. She has to let the Disney dream go to take hold of the unexpected partnership that fulfills her desires. Samantha is the bold, promiscuous go-getter who enjoys sex in the same way men do. She rejects the idea of a committed relationship (for the most part) because she doesn’t need a man for anything other than sexual intimacy, and that usually has an expiration date. When a young heartthrob surprises her and stands by her side during the most vulnerable time of her life, she recognizes that it is possible to have genuine companionship and sexual chemistry with a man without sacrificing a damn thing. And then there’s Carrie.

Everyone wants to be like Carrie, but no one wants to be like Carrie. This is for many reasons, but the main reason is she is both deeply flawed and undeniably lovable. She’s funny, intelligent, dynamic and has incredible taste. She is also needy, selfish, aloof, judgmental, and stubborn. Carrie is the only character on the show who does not neatly fit into an archetype. For this reason, Carrie isn’t like most main characters on television, or rather, she isn’t like most female characters we’ve seen on television. She’s written with so much nuance and humanity that it is hard for many of us to digest her without diagnosing her. I don’t read nearly as many think pieces about Tony Soprano being a sociopath despite his murderous tendencies as I read and watch character assassinations on Carrie for being a “narcissist.”

Yes, Carrie makes horrible life decisions. She isn’t ashamed to pair bra straps with her spaghetti strap tank tops. She’s constantly strapped for cash because she has a genuinely concerning addiction to Manolo Blahniks. She smokes relentlessly, even behind her perfect boyfriend’s back. She cheats on the same boyfriend, gets back together with him, then gets engaged to said boyfriend only to reject him once again in a beautiful white gown fit for a fashion girl’s wedding. Carrie asks us to challenge our idea of what it means to be a good person or to live a good life. In a media culture that loves good vs. evil narratives, SATC still feels refreshing to watch because its protagonist is a woman with a good heart who doesn’t always lead with it or listen to it. However, with all of her flaws, Carrie is an undeniably good writer. She is able to take her all of her experiences, all her friends’ wisdom, and share those lessons with her readers in the hopes that they may learn from her mistakes. And I thought to myself, shouldn’t that be good enough?

To those who don’t understand Carrie, and I would dare to say that accounts for most SATC viewers, she had the least amount of growth as a character. Although she is the protagonist, narrator, and symbol of the show and its titular column, she is the only character who lands right where she started—into Mr. Big’s arms. What we forget is that Carrie’s narration of each episode stands in for the articles which are meant to accompany them. Her character arc is the development of her column. Her growth as a writer is built upon these stories she is supposedly writing on that MacBook, at that wooden desk in front of her bedroom window. Throughout the series, we listen to her observations on the world as they become more focused and introspective. In the first season, she is talking directly to camera. She breaks the fourth wall to engage us, the audience, as her readers. As the show progresses, the fourth wall closes in. She is still narrating the scenes, but we are now in the room with Carrie and her friends during their most intimate moments. Everything we watch unfold in the women’s lives, we are meant to interpret it as an extension of Carrie’s research for her column. Sex and the City is as much about love, friendship and sexuality as it is about the creative process.

Mr. Big is Carrie’s greatest muse. Big is the wealthy, successful, handsome bachelor that everyone in town wants to tie down, including Samantha. He is the perfect constant for Carrie to dissect in her ongoing study of human sexuality. The only issue is that Big is not who Carrie assumes he is. He does not answer her questions in the way she expects. When she formally meets Big towards the close of the pilot episode, he asks her what she does for work, and her response is, “This is my work. I’m sort of a sexual anthropologist.” She is being cheeky, but her work is serious. Carrie isn’t just having sex or falling in love for the fun of it. She’s researching the very sexual drive itself, uncovering the root of why we love and how we express love to one another. When Big calls her bluff and says, “I get it. You’ve never been in love,” Carrie has the wind knocked out of her. Before meeting Big, Carrie could intellectualize romance and write about it as an unbiased observer because she herself had never known what it was like to have sex with someone she actually loved. Instead of analyzing her own misfortunes in love, she interviews her friends and writes about their experiences as inspiration for her column. Now, things are personal. For the first time, Carrie meets her match. The real writing begins.

In the back of Big’s town car, Carrie tells him about her research, and he immediately foils her hypothesis. He tells her that she isn’t the kind of person who can have sex without feeling, and neither is he, “not one drop, not even half a drop.” After Big’s chauffeur drops Carrie off in front of her apartment, she begins to walk off but suddenly turns around with an inquisitive look on her face. She knocks on his car window and asks, “Have you ever been in love?”

“Abso-fuckin-lutely.” Big says with total confidence. He drives off into the night.

If that’s the case, if one of the most powerful, most eligible bachelors in New York has been in love and must be in love with the women he has sex with, why is he still single? Thoughts begin to flood Carrie’s mind. He frustrates her in a way only a loved one can. He is a riddle Carrie tries to solve throughout the six seasons of the series.

Big is not just a man, but an idea1. Like an abstract thought you struggle to grasp and articulate into words, Carrie cannot read Big, but he can read her almost immediately, which is what intrigues her. To understand Big would be to understand the male psyche at its peak. She is drawn in close, intending to study him while remaining impartial. What she does not expect is to fall in love with the subject. She loses control and fights to get it back, but it is too late. The love story is writing her rather than the other way around.

If Big is the subject of her work, Carrie’s friends, Samantha, Miranda, and Charlotte, all shape the work she writes by sharing their feedback, their advice, and their experiences with her. Carrie’s relationship with her friends is like any writer’s relationship with her editor. They read the work, markup the work, and the writer goes back and makes changes–or doesn’t. To understand Carrie is to understand the inner life of a writer.

In Jamie Tarabay’s article for The Atlantic, “Television’s Puzzling Fixation on Women Who Are Writers,” she examines the parallels between Carrie Bradshaw and Hannah Horvath, the protagonist in HBO’s hit series Girls, created by and starring Lena Dunham. Tarabay asks, “Does this mean that creative people are the only ones who really question their destiny, their identity, and their sexuality?” Tarabay believes this is a rhetorical question, with the assumed answer being no. I would argue that creatives are, in fact, the only ones in our society who are paid (or not) to think critically about life and the human condition in ways the average person cannot or would not think about.

Sexuality is directly tied to our creative drive and vice versa. In Carol S. Pearson’s book Awakening The Heroes Within, she says about libidinal energy,

“Love is about joy and pleasure, and it is also about birthing. On the most psychical level, sexual passion often results in the conception and birth of a child. But it is not just psychical birthing that sex creates. Eros often attends the creative process.”

Carrie meets Big just as she begins her research for her column. Her on and off again romance with Big is what motivates her to complete her research, develop her column, and finally publish her column as a book. It is when she’s with partners like Aidan or Alexander Petrovsky that she is her least productive as a writer because she is not challenged intellectually or emotionally. For any normal person, this would be the goal, but not for a writer. To be a writer is to seek critique, to desire to be challenged, edited, questioned. The writer in love is also in labor. Every conversation, every memory, every detail of this romance is a story waiting to be told.

Apart of what made Carrie’s friends so frustrated with her is that she was sitting around pondering about Big, about love, about relationship dynamics and asking them to have conversations with her to help her process these thoughts while they had their own lives to live. Writers never want to stop writing the work. There are always a million more ideas that can be brought into the essay, or old sentences and words that seem outdated and could be redacted or changed. Editors are there to keep writers from going off the deep end. They are there to remind the writer that there is a deadline. The work doesn’t have to be perfect, it just has to get done.

Unlike Carrie, her friends do not have the luxury of thinking for a living. Miranda is a lawyer and became a wife and a mother. Samantha is a powerful PR executive and breast cancer survivor. Charlotte is an art dealer who got married, got divorced, marries her divorce lawyer, and struggles with fertility. They, like most normal people, are too busy living life to zoom out and analyze it everyday. But self-analysis and existential thinking is the nature of Carrie’s job. Her writing is her baby. It consumes her life, probably because her life is the subject of her work.

When a writer is in the flow of writing a piece, she is transported to another world. It is much like good sex. You enter a state of being that is outside of time and space. You cannot be concerned with the practical problems of the world. Any distraction could break your focus from the work. You must do the alchemy of bringing every abstract thought, every invisible image, down from the clouds and onto the page. For this reason, writers are often aloof, distant, and hard to pin down. Sometimes being a good writer means being a lousy friend, an absent lover, and a disengaged member of society. It’s not always because writers are narcissists or self-absorbed. More often than not, it means they’re working on something so good, so consuming, that they are unable to be present on earth until they birth the vision growing inside their minds.

Carrie was loyal to her friends and made them the subjects of her work. They understood her and they were patient with her because they loved her and they respected her craft. They respected her work so much that they volunteered to be apart of her column, sharing their stories and perspectives not only with Carrie but with her readers. Miranda, Charlotte and Samantha were not the independent variables in Carrie’s experiment, but the constants. In the dedication to her book, she wrote: “To single women everywhere, and to one in particular… my good friend Charlotte, the eternal optimist who always believes in love.”

“So which character are you?” My friend asks me as we are on the subway heading to our undergraduate classes. We took the Statistical “Which Character” Personality Quiz, which is not specific to any show, and I still received a 77% match to Ms. Bradshaw. I’m afraid to share the answer because I am embarrassed to admit the truth. I am a Carrie. I am a writer. I have big curly hair. I am a fashion hoarder who spends her last dollar on vintage designer clothes from Beacon’s Closet and eBay instead of saving it to pay the rent. I am aloof and disorganized, but not with my thoughts or my fashion. Those may be the only elements I have any control over in my life.

My family and friends know that if I go missing for months on end, it is likely because I am busy working on a project, or processing my tangential thoughts piece by piece to then put them down on paper. They know I will one day reappear and come down from the mountaintop bearing new gifts for them to read and discuss. I was raised by my mother and her best friends. They are all perfectly imperfect and love each other fiercely, just as the ladies of SATC did. These women are my village. They showed me that your friends really can be your soulmates. God bless them for putting up with me.

“The most exciting, challenging and significant relationship of all is the one you have with yourself. And if you can find someone to love the you you love, well, that's just fabulous."

— Carrie Bradshaw

An excerpt from Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, Book I, “The Data of Biology,” Pg. 61: “It is only in a human perspective that we can compare the female and the male of the human species. But man is defined as a being who is not fixed, who makes himself what he is. As Merleau-Ponty very justly puts it, man is not a natural species: he is a historical idea. Woman is not a completed reality, but rather a becoming, and it is in her becoming that she should be compared with man; that is to say, her possibilities should be defined. What gives rise to much of the debate is the tendency to reduce her to what she has been, to what she is today, in raising the question of her capabilities; for the fact is that capabilities are clearly manifested only when they have been realized–but the fact is also that when we have to do with a being whose nature is transcendent action, we can never close the books.

I am a big SATC fan and this is the best essay I have read so far❤️Thank you for sharing.

Such a good essay! I always feared I was a Carrie despite aspiring for an interesting Samantha/ Charlotte mix. The test you suggested confirmed it, 80% Carrie with the others trailing 10% or more behind.

I love the grace and thoughtfulness you gave to her though. Def gave me a new perspective on the character 💕